Revision Total Knee Replacement

Revision Total Knee Replacement

Revision Total Knee Replacement

Total knee replacement (TKR) surgery, like total hip replacement is one of the most successful and life changing operations performed. Because of this many hundreds of thousands are performed worldwide. As implants and the materials they are made from have been improved more and more knee replacements are being performed on an ever-younger population. Combined with increased activity levels and patient expectations and the ever increasing life expectancy of the population, more demands are being put on the implants than ever before.

Unfortunately artificial joints will eventually fail. The length of time the knee replacement has been in use combined with activity levels and the amount of forces going through the knee replacement (related to how much you weigh) are all important factors that can lead to joint replacement failure.

Revision total knee replacement is very challenging surgery involving large amounts of equipment and should only be performed in centres that have all the necessary instruments and implants available for any eventuality.

The outcome of revision TKR is nothing like as good as first time knee replacement (primary) surgery (roughly half as good) and all the perioperative risks associated with primary surgery roughly double. This is why it is important to consider the indications and timing of your primary surgery very carefully and avoid surgery if at all possible, especially if you are young.

Most common reasons for knee replacement revision:

Aseptic loosening

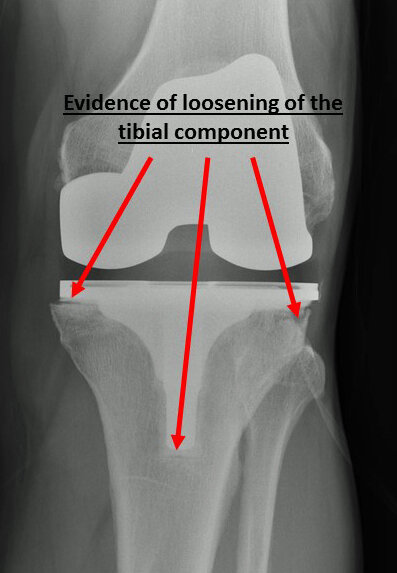

Knee replacements can fail by becoming loose (aseptic loosening) within the bone resulting in abnormal movement of the implant.

This can be related to failure of the tibial insert polyethylene (PE) bearing that sits between the metal femoral and tibial components (see Total Knee Replacement). Modern PE is exposed to various procedures during its manufacture such as annealing and crosslinking of the PE molecules to try and increase its longevity and minimise wear particles. It is thought the wear particles produce an inflammatory response than results in lysis (softening and destruction) of the bone around the implants that can cause loosening. Sometimes the PE insert delaminates and fractures resulting in catastrophic joint failure.

Infection

Very rarely loosening and failure can be caused by and infection in the knee replacement (septic loosening). This can be as result of direct infection acquired at the time of surgery or as a result of secondary spread in the bloodstream from another source of infection in the body such as a tooth abscess or urinary tract infection. If you had a problem with a wound infection that required antibiotics at the time if your initial knee replacement and subsequently develop a painful, hot, swollen knee then infection needs to be ruled out as a matter of urgency.

The symptoms and signs of a failing knee replacement are often pain, swelling, stiffness and increased warmth and sometimes redness in the knee.

This can cause pain and swelling of the knee. If left unchecked the bone surrounding the implant can become damaged resulting in loss of bone stock. This can make the revision (re-do) knee replacement much more difficult as there is less bone available for fixation of the new implant.

The diagnosis of infection can be challenging, especially if you have been given previous antibiotics before samples have been taken but may include:

Inflammatory Markers in the Blood

These are nonspecific markers of inflammation in the blood but if raised increase the suspicion of infection and include:

C Reactive Protein (CRP),

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR)

White Blood Cell Count (WBCC)

Knee Aspiration in Theatre

Particularly if the inflammatory markers are raised fluid is aspirated out of the knee under local anaesthetic in the clean environment of the operating theatre to reduce risk of contamination. The joint fluid (synovial fluid) is sent off for laboratory analysis to look for bacteria and white blood cell count (WBCC) in the sample (microscopy) and culture to see if any bacteria subsequently grow. Identifying the causative organism and appropriate antibiotic sensitivities helps guide further treatment and can help decide whether a one stage or two stage revision is appropriate.

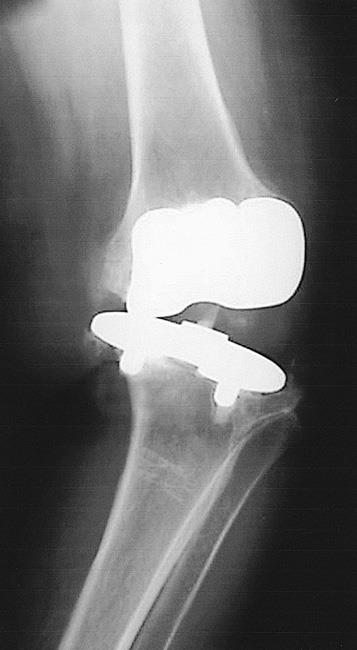

Plain Radiography (x-ray)

A plain x-ray of the knee replacement may show signs of implant loosening (lysis) with loss of fixation of the implant to the bone and sometimes movement of the implants in the softening bone. This is as a result of the infection inducing abnormal inflammation within the knee resulting in destruction of the supporting bone. This has to be distinguished from non infected (aspetic) loosening as discussed above.

Isotope Bone Scans

If changes are not apparent on plain x-rays radionuclide imaging can be helpful in helping diagnosing loosening and infection of the implant. This involves the injection of a small amount of radioactive fluid which is taken up by the bones in areas of high bone turnover (such as in infection or loosening). A scan is performed approximately 3 hours later to see which areas of your skeleton show increased uptake. If there is increased uptake around your knee replacement it may indicate loosening or infection.

More specific tests for infection include a White Blood Cell Scan which involves labelling your own white blood cells with a radioactive tagging agent (eg Indium 111) that localises in areas of infection.

Once the diagnosis is confirmed the infected implants will need to be removed and the tissues and bone debrided and cleaned in order to clear the infection.

A decision will be made on whether a one stage or two stage revision will be performed depending on the identification of the infecting organism and its sensitivity to antibiotics.

What is a one stage revision?

Once the infected implants and all cement have been removed the soft tissues are thoroughly debrided to remove all visibly infected tissue. Multiple samples are sent to the laboratory for analysis to guide antibiotic treatment. The new revision implants are then inserted often with specific antibiotic loaded cement. Antibiotics are often given intravenously via long line fro a period of 6 weeks depending on response to inflammatory marker blood testing.

A one stage revision offer a quicker return to function and recovery but has a slightly higher risk of the infection returning.

What is a two stage revision?

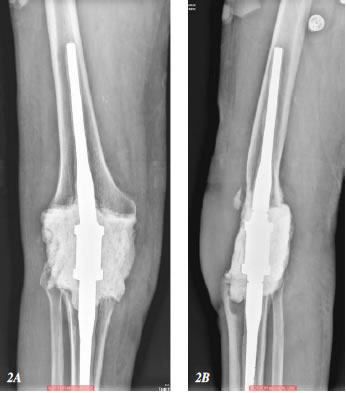

The ‘gold standard’ of treatment for infection is a two stage revision. After implant removal and debridement (as in a one stage revision), instead of implanting the new prosthesis, an antibiotic loaded cement spacer is inserted into the joint space. This delivers sustained antibiotic locally to the joint over a period of weeks in conjunction with intravenous therapy and acts to keep the joint space ‘open’ in preparation for reimplantation of a prosthesis. The antibiotic loaded cement joint spacers can be shaped like a knee replacement to allow movement and maintain soft tissue length and flexibility (dynamic spacer) or if there is too much bone loss the spacer is used with a rod that crosses the knee joint on the inside to maintain stability but doesn’t allow any bend (static spacer).

The spacer is left in for 6-8 weeks and once the infection has been treated, removed and the revision implants are inserted.

A two stage revision offers a slightly higher success rate of resolving infection but is a much more protracted treatment regimen than a one stage revision.

Instability

Instability after knee replacement surgery can cause pain, swelling and loss of function and loss of confidence in the knee. In extreme cases it can cause “giving way” when the knee collapses particularly when pivoting on the knee such as when changing direction whilst walking.

Causes of knee instability can include loosening or malposition of the implants as well as over or under sizing the implants. Stretching of the knee ligaments over time or damage caused by an injury to the knee resulting in their rupture can also lead to instability. Excessive polyethylene wear over time can result in loss of soft tissue balance in the knee and can result in instability. Sometimes a failure to balance the soft tissues adequately at the time of the original knee replacement is the problem.

Stiffness

Persistent stiffness (reduced range of movement) following knee replacement surgery can be very problematic and is difficult problem to treat. Approximately 5-10% of patients develop stiffness after a TKR. The reasons why some patients develop stiffness is poorly understood and often unexplained as everything appeared to have gone well with the surgery and postoperative x-rays appear entirely satisfactory but despite this there is limited movement in the knee which is often also painful.

Revising a knee replacement for unexplained stiffness can often result in a poor result and as the perioperative risks double with revision knee surgery should be performed with extreme caution.

However it is important to exclude other treatable causes for stiffness, particularly infection and component malposition or sizing problems as well as soft tissue problems such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and arthrofibrosis.

What is Arthrofibrosis

Arthrofibrosis is when excessive scar tissue develops within the knee which can cause significant stiffness and functional impairment. Patients who have a long history of reduced knee movement preoperatively and those undergoing longer, more complex surgery are more at risk of developing arthrofibrosis.

Also immobilising the knee postoperatively risks a build up of scar tissue which is why it’s important to keep moving your knee despite the pain after surgery in order to minimise this risk. The build up of scar (fibrous) tissue within the knee gradually thickens and contracts thereby limiting movement.

Treatments include

Manipulation Under Anaesthesia

The scar tissue is broken down by manipulation whilst the patient is anesthetised to regain range of movement. This requires intensive postoperative physiotherapy and often the use of a continuous passive motion machine (CPM) to prevent recurrence.

Arthroscopic Surgery (Key Hole)

Sometimes the scar tissue inside the knee can be excised using minimally invasive techniques such as arthroscopy (arthrolysis).

Open Arthrolysis

In the most severe cases open excision of the scar tissue can be attempted. However intensive physiotherapy is required postoperatively and CPM to try and prevent the re- accumulation of the scar tissue and is by no means always successful.

Trauma- Periprosthetic Fracture (PPF)

The management of a fracture (break in the bone) around a total knee replacement can be very challenging. There are several factors which can influence the management. These include the pattern and location of the fracture in relation to the knee prosthesis as well as the quality of the surrounding bone and the normal activity levels of the patient.

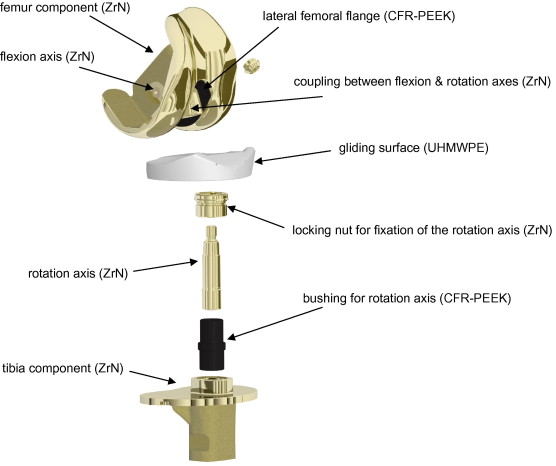

If there is very little remaining bone fixed to the prosthesis or if the prosthesis has become loose as a result of the fracture, then revision with a new prosthesis, rather than fixation of the bone with plates and screws is indicated.

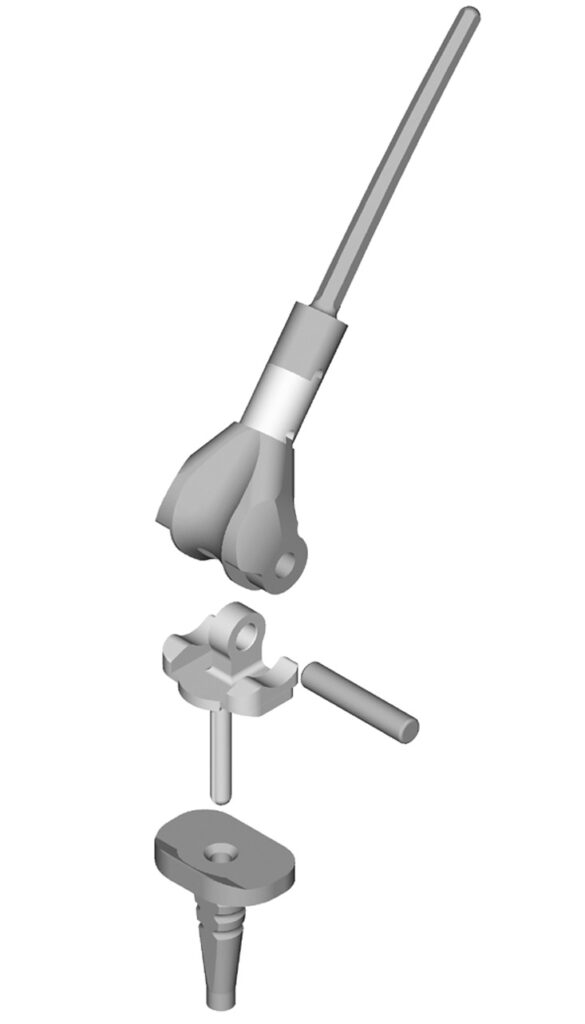

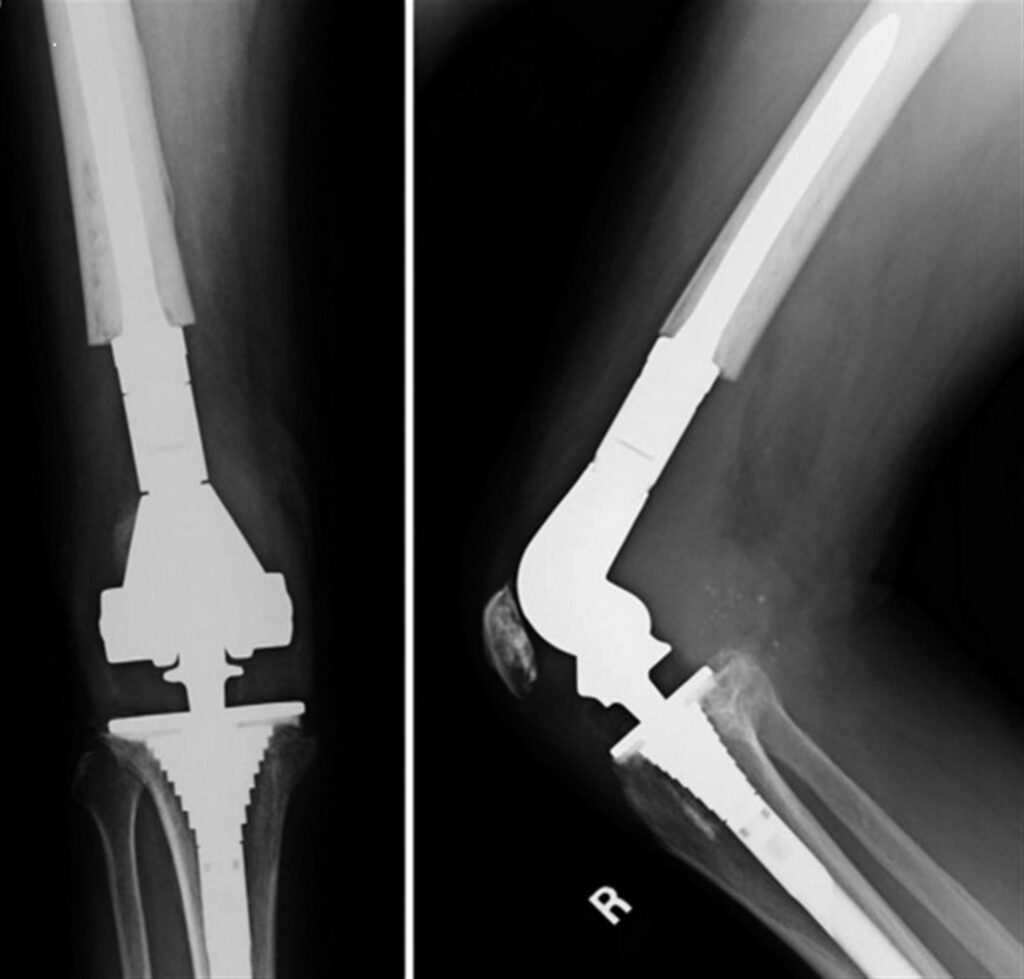

In these cases the entire end of the femur (thigh bone), including the knee joint is replaced with one prosthesis that is physically linked to the tibial component for stability (Distal Femoral Replacement). These type of mega prostheses were initially designed for tumour surgery, where large segments of bone including the adjacent joint needs to be excised en bloc with clear margins. However the same techniques can be used after PPF where fracture fixation is not suitable in order to allow immediate weight bearing following surgery. This is particularly important in the elderly who can find partial weight bearing on one leg whilst a fracture heals very difficult.

Challenges in Revision TKR

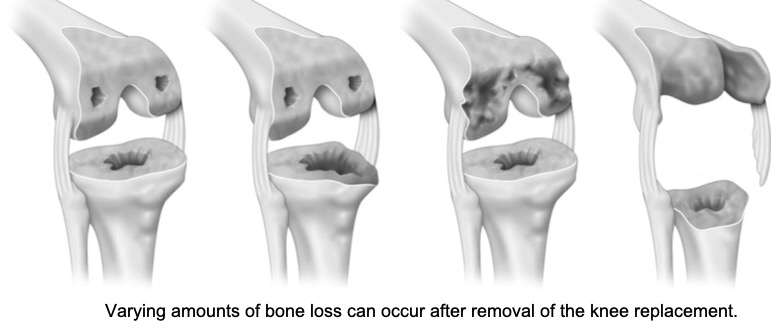

Bone loss

Bone loss can be as a result of extensive osteolysis (thinning) of the periarticular bone as discussed above or as a result of the trauma of removing the original prosthesis or fracture of the periarticular bone as a result of injury or often a combination of these factors.

Obtaining secure fixation of the new implant when the remaining bone stock is reduced can be challenging.

There are different designs of revision knee replacements in order to overcome these challenges.

These include:

- Long stemmed implants which are either cemented or uncemented (press fit) to increase fixation by increasing the zone of fixation to the shaft of the femur or tibia.

- Metaphyseal sleeves are designed to be impacted into the ends of the femur or tibia where most bone loss is present. These can “grip” the remaining bone, resulting in secure fixation even in the presence of significant bone loss. Their surfaces can be porous which facilitates the bone growing onto it adding to the initial press-fit fixation.

- Augments are shaped metal blocks that can be attached to the revision prosthesis to fill in the gaps in the bone in order to provide added support at the implant bone interface.

- Impaction bone grafting using bone chips in a similar technique as described for the hip can sometimes be used to replace bone if the defect is contained. However it is less common for the bone loss to be contained in knee revision surgery than it is in revision hip surgery.

Often these techniques are used in combination depending on the nature and extent of the bone loss.

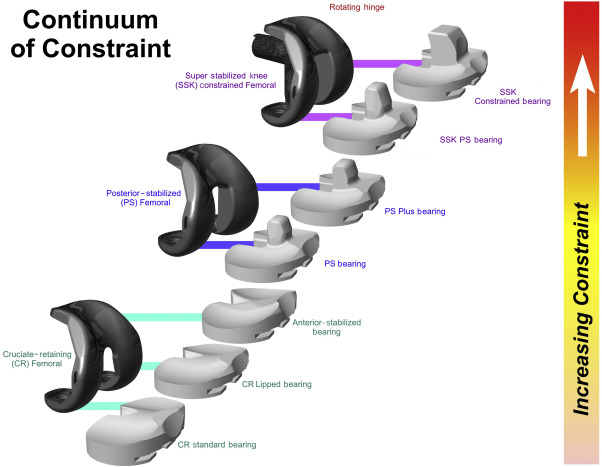

Soft tissue imbalance

The soft tissues surrounding the knee are often abnormal as a result of the previous surgery. This can make soft tissue dissection and exposure of the knee difficult and sometimes as a result the ligaments are found to not be functioning normally which can result in a wobbly knee (instability). If not recognised and dealt with at the time of revision the knee would not function normally and would collapse when bearing weight. In order to compensate for varying degrees of instability often encountered at revision knee surgery there are different levels of constraint designed into the revision implants.